Former UEFA president Michel Platini always opposed the introduction of technology in football because he felt that, once it gained a foothold, it would quickly expand and change the character of the sport altogether.

Football, he warned, was about to open Pandora’s Box.

Several years later, the Frenchman may feel he has been proved right by the pervasive use of video assistant referees (VAR).

When it initially presented VAR in 2016, soccer’s rule-making body IFAB said the purpose was to stamp out glaring refereeing mistakes such as Diego Maradona’s Hand of God goal in the 1986 World Cup.

But, less than 18 months after its introduction, it has turned into what seems a search for refereeing perfection.

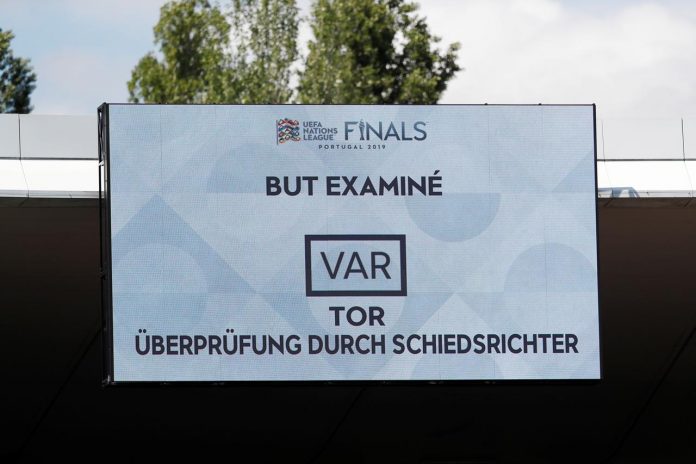

Matches are now stopped for two to three minutes and goal celebrations put on hold while VAR officials in a room full of television monitors conduct a forensic examination for the slightest hint of contact or offside in the build up.

England had two goals disallowed after VAR reviews at the Nations League in Portugal when not even their opponents complained of an infraction.

Callum Wilson’s late goal against Switzerland on Sunday was chalked off after VAR spotted that he pushed Manuel Akanji in the buildup while Jesse Lingard’s effort against the Netherlands was ruled out because part of his body was a fraction offside.

Similarly, in the women’s World Cup, Griedge Mbock Bathy had a wonderful strike for France disallowed against South Korea because the tip of her foot was ahead of the last defender even though the rest of her body was line.

All three decisions were technically correct but was that what VAR was intended for? And were they in the spirit of the offside rule which is designed primarily to stop forwards goal-hanging?

When preliminary testing began, IFAB’s technical director David Elleray said that “VAR isn’t designed to end referee mistakes but it’s to deal with those very clear match-changing ones.”

As an example, he cited Thierry Henry’s goal, scored after he controlled the ball with his arm, which took France to the 2010 World Cup at Ireland’s expense — hardly the same as a player having their finger three centimetres offside.

OBVIOUS ERRORS

In a briefing to reporters earlier this year, UEFA’s refereeing chief Roberto Rosetti said that the incidents were reviewed if they obvious to VAR officials — not simply players, coaches or spectators.

Linesmen are now told to keep their flags down when they suspect an offside so the incident can be reviewed in the studio once the move finishes, effectively reducing their role.

Sometimes, VAR can be as controversial as a decision taken with the naked eye, such as the penalty awarded to England against Scotland in Sunday’s women’s World Cup match for handball by Nicola Docherty when there seemed no way she could get her arm out of the way.

Equally contentious was a penalty given to Switzerland against Portugal in the Nations League for the slightest of tugs on Steven Zuber.

Former World Cup final referee Arnaldo Cesar Coelho warned last year that slow motion could make fouls and handballs appear deliberate when they really were not.

“Slow motion distorts the incident because it does not always the reflect the intensity of the movement,” he said.

The Zuber incident raised another awkward question — when to stop play for a review — after Portugal immediately broke down the other end and were awarded a penalty of their own. Amid huge confusion, Portugal’s penalty was revoked and a spot kick awarded to Switzerland.

Portugal coach Fernando Santos suggested that VAR was a good idea — but only if properly used. “I think VAR is important, I think it can help but those who are in charge have to pay attention to this,” he said. “Otherwise we will all start saying that VAR is no good when it could be a really useful tool.”