There has been plenty on Angelo Mathews’s shoulders in recent times. This is not just a metaphor. As he leans back on a plastic chair, his tanned biceps roasting in the Colombo sun, it is surprising to see the prairie of dark hair that runs from the back of his black and orange singlet, reaches just over the tips of his collarbones, and spreads down the back of his arms.

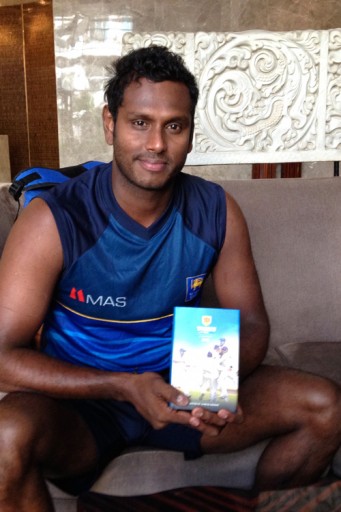

Mathews has been Sri Lanka’s boy-next-door heart-throb ever since he leapt into the national consciousness with a piece of sublime boundary fielding at the 2009 World Twenty20 in England. Now 27, and established as a classy batsman and nimble-witted seamer, Sri Lanka’s youngest captain has indisputably become a man.

He is at Tyronne Fernando Stadium in Moratuwa, in the southernmost reaches of his city, shooting a commercial for a new chewing-gum sponsor whose precise name escapes him – Centerfruit or Centerfresh? We talk between takes: batsman, bowler and leader, Mathews has become accustomed to juggling duties. After the Sri Lanka Cricket Awards in September 2014, he was swarmed by well-wishers, but unable to shake hands above thigh-height, so laden were his arms with prizes.

“I know I’ve had a pretty good year,” he says, shifting forward in his chair and pausing long enough for beads of sweat to form on his upper lip. Only pretty good? The reticence is almost expected: it has become a personal characteristic, in step with a dislike of bluster. But you feel there is a little more at play. A chronic sufferer from the nervous nineties, Mathews was once easy to cast as a selfish batsman. The accusation is no longer valid.

ANGELO DAVIS MATHEWS was born in Colombo on June 2, 1987. He grew up playing cricket, and first attracted attention as one half of St Joseph’s College’s fearsome fast-bowling pair in schools cricket, alongside Tissara Perera, now a fellow all-rounder in the national side. Mathews captained his school team in 2006, when he also led Sri Lanka’s Under-19 side at the World Cup. He was snapped up by Colts Cricket Club, graduated immediately to the first-class game, and was called up by his country for a tour of Zimbabwe in 2008.

Last year, he was at the heart of almost every Sri Lankan success. Perhaps the most staggering aspect of his performances in 2014 – when he averaged 77 in Tests and 62 in one-day internationals – is that it included knocks such as his 18 off 90 balls at Lord’s, where Sri Lanka grabbed a draw. Since taking the reins in early 2013 – his Test average of 76 as captain is second only to Don Bradman among those who have led in more than six games – Mathews has been finely attuned to his team’s pulse. From stonewall to rampage, on greentop or dustbowl, he has adapted accordingly. Against Pakistan in Abu Dhabi at the start of the year, he seared 91 on the first day as colleagues crashed around him, then slow-cooked 157 in the second innings to save the match. His monumental batting returns since then are the result of some delicate self-improvement.

That aim achieved full expression in the Second Test against England at Headingley, but not before he had played a major part in salvaging the First at Lord’s. Mathews had arrived in the first innings at four down, with Sri Lanka still trailing by 286. He made 102, laying out a major theme of his year – prising runs from opponents’ closed fists with only the lower order for company. A place on the honours board beckoned, but Mathews was declining easy singles in his nineties.

“I wasn’t thinking about the hundred, and that possibly helped me to get there. It was very satisfying to do it in such a special place, but for me it was about playing positively. You can’t play to just survive in England. At any time you could get a very good ball and be gone.”

Sri Lanka had felt besieged – by the reporting of Sachithra Senanayake’s action, and the fallout over his Mankading of Jos Buttler during the Edgbaston one-dayer. Barbs fired by the England team, on and off the field, did not help. Mathews resolved to fight back. “We’ve won the ODIs and the T20,” he told his team before the Second Test. “We can do this. Let’s be aggressive. Don’t take a backward step.”

At Headingley, Mathews took a career-best four for 44. But on the fourth afternoon he found himself throwing his bat to the ground in disgust as Sri Lanka’s second innings threatened to disintegrate. Often stoic, rarely severe, he now harnessed his emotions. In one hand he held a sledgehammer, for mowing fours; in the other a scalpel, for laser-like incisions through England’s ring field. His eighth-wicket stand of 149 with Rangana Herath would help double Sri Lanka’s lead towards 350. In one afternoon Mathews had transformed the series.

“That was definitely my best batting in Tests,” Mathews says. “It was one of those days when everything I tried went smoothly. Once we passed a lead of about 200, that freed both me and Rangana aiya [elder brother] up even more, so we just started going for it.”

The win at Headingley, off the penultimate ball, shot Sri Lanka to a historic triumph. It was only Mathews’s fourth Test series at the helm. For that, and his exceptional batting, he would be named captain of the ICC’s annual Test XI – an accolade unthinkable after his self-confessed negativity earlier in the year had led Sri Lanka to a dispiriting defeat as Pakistan squared the series in Sharjah.

He knows his greatest challenges as leader are yet to come. “I’ve learned a lot, and I will keep learning as long as I’m playing cricket.” As his shoulders show, 2014 was a year of irrepressible growth.